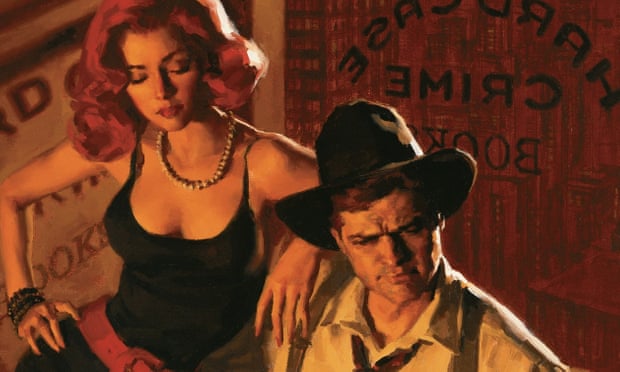

As political corruption, violence and gender politics gain fresh relevance, pulp noir is attracting new voices and audiences, giving the gumshoe a 21st-century reboot.

Back in 1920, Henry Louis Mencken and George Jean Nathan ran a magazine for the well-heeled women and their sugar daddies up on Long Island: the Smart Set, they called it.

The Smart Set wasn’t doing so well – but Mencken had an idea. He had noticed that a periodical called Detective Story Magazine, was flying off newsstands, so he started his own crime pulp: Black Mask, the first issue of which landed in October 1920, complete with a woman being menaced with a burning branding iron on the cover.

Mencken had no illusions about Black Mask, writing to a friend that it was “a lousy magazine” but “it has kept us alive during a very bad year”. After just eight issues, Mencken and Nathan sold it on to a Madison Avenue publishing company – but there it pioneered a brand new genre: the hardboiled detective story.

Hardboiled is all about cynical, complex detectives; think of Humphrey Bogart’s turns as Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe or Dashiell Hammett’s private eye, Sam Spade. What’s now considered the first hardboiled story was published by Black Mask in 1922: The False Burton Combs, written by Carroll John Daly (“I ain’t a crook; just a gentleman adventurer and make my living working against the law breakers. Not that work I with the police – no, not me. I’m no knight errant either.” The archetype was born: men out for justice and/or revenge, pounding perpetually rainy streets in a dark American city. But isn’t he an anachronism today?

“I suspect he always was,” says author Lawrence Block, who has been writing noir for 60 years. “Which is not to say that there aren’t a fair number of such lads walking around at present. I suppose the character owes much of his appeal to being the sort of person the reader would be if he could.”

Amid an explosion of pulp crime magazines – Dime Detective, Detective Tales, Strange Detective, Ace G-Man Stories – in the 20s and 30s, Black Mask would publish some of the greats: Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, early stories by Chandler, and Erle Stanley Gardner. As postwar paperbacks took off in the 50s, the market began to decline, but some periodicals endured – including Manhunt, on which a teenage Block got his big break in 1957, with You Can’t Lose. Now 78, Block is the writer behind creations including alcoholic ex-cop turned private eye Matthew Scudder and gentleman burglar Bernie Rhodenbarr.

Isn’t it tough to make readers embrace heroes with ambiguous morality? “Is it?” says Block. “I wonder. I guess I assume that if I can sympathise with a character, so can a reader. And if I can’t connect with the essential humanity of any of my characters, then I’m doing something wrong.”

Article continues here:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/mar/23/detective-fiction-hardboiled